Internment of Sick and Wounded Prisoners of War in Swiss Hotels During World War One.

Dr Susan Barton (honorary visiting research fellow, De Montfort University) – subarton@btinternet.com

Dr Susan Barton, honorary visiting research fellow at De Montfort University in Leicester, is investigating the intersecting histories of diplomacy, the role of a neutral nation in war, imprisonment and internment, tourism, leisure, gender and sport. The Swiss hotel is at the nexus of this research programme. One of the aims of the project on the internment of POWs in Switzerland between 1916 and 1919 is to fill a lacuna in tourism history, the gap between the pre-First World War and post-war periods, the times when other histories either end or begin, ignoring the impact on the industry of the war.

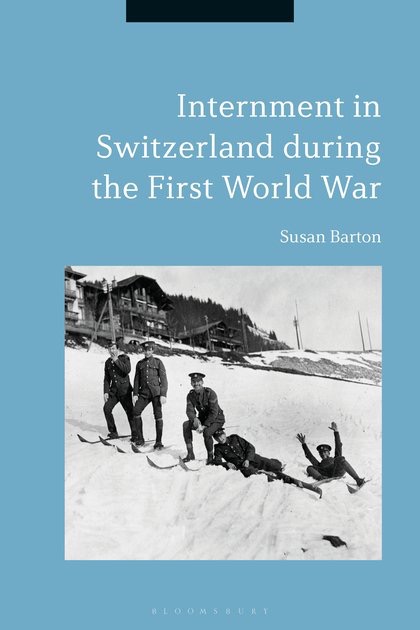

The project draws on a variety of sources. Records in the British National Archives give an insight into the political and diplomatic negotiations leading up to the agreements between the warring nations and Switzerland to exchange sick and wounded prisoners who were likely to recover and to intern them in Swiss hotels. Monthly reports despatched to the War Office by interned Senior British Officers give information about routines, discipline and behaviour of internees and approved activities such as training, education, work and sport. Documentation in Swiss archives and collections, and reports written by Belgian, British, French and German internees in their magazines Journal des Internés Français, Deutsche Internierten Zeitung, and British Interned Magazine provide evidence of the preoccupations, interests, sports, entertainment, social life, marriages, births and deaths within the internee communities. These records are supplemented by letters, photographs, certificates and memorabilia in personal, family collections owned by descendants of interned POWs. Internment provided opportunities for cultural exchange and transfer between Swiss French and German speakers, interned Belgian, British, French, German soldiers and colonial troops from Canada, India and Africa. Unlike other forms of imprisonment for POWs and ‘enemy aliens’, interment in neutral Switzerland did not involve being locked up or kept behind barbed-wire fences. Internees there could mix with local people, including women, or have their own female family members stay with or visit them. Experiences have been found to have been remarkably similar for all internees, whatever their nationality. A number of themes are being explored as part of the project.

The project explores negotiations between the warring nations and the Swiss government with the help of the International Committee of the Red Cross that led to agreements to exchange sick and wounded prisoners of war. Initially this was to allow the most seriously injured to be transferred from prison camps in Germany and France across Switzerland for repatriation. The impacts of the war within the context of Swiss neutrality and the problems this presented in terms of partisanship and how these were addressed have been investigated. The concerns of the Swiss tourism industry, struggling because there were fewer visitors, led to wounded interned soldiers being accommodated in hotels which provided a reduced revenue that kept them afloat through the war years. This helped many hotels survive despite problems paying repaying loans used to expand premises and tourism infrastructure in the boom years of the previous decade.

The project is investigating the day-to-day conditions of internment in Swiss hotels, the rules and regulations for ensuring good conduct, food rations and how internment was funded. Some internees suffered from psychological problems after their experiences of war, wounding, imprisonment and then the sudden release from prison into the relative freedom of Switzerland. Others were bored with little to occupy their time. A minority caused problems because of alcohol abuse and measures had to be introduced to address the anti-social behaviour caused by drunkenness and alcoholism. Unlike civilian internees, prisoners of war were obliged to work. Officers were exempt from this obligation, although in Switzerland many chose to occupy themselves by supervising and facilitating activities for their men. Employment helped relieve boredom but also prepared those with life-changing injuries to be self-supporting after the war. Many wounded and mutilated men would not be capable of returning to their former jobs when they arrived home. Efforts were made to provide retraining for these men. Some of them had little formal education and lacked basic skills, a problem addressed by special classes, including literacy. Others were able to learn new skills to take advantage of new technologies like the motorcar. Those with an academic background could continue their studies in Swiss universities. These opportunities would give disabled men more of a chance of finding work after the war.

As in civilian and prisoner of war camps, internees in Switzerland formed clubs and developed league systems for football and cricket. They enjoyed boxing, tennis and other activities. Unlike in other forms of imprisonment, sport provided opportunities to travel beyond their own internment centre for away games, international encounters with allies of a different nationality, Swiss teams and individual sportsmen. Matches and tournaments provided opportunities for spectators to pass their time. In some sports, such as tennis, wives and other family members could also join in. Sport helped in the physical rehabilitation of damaged bodies, helped develop strength and fitness and self-esteem. For those who were successful in sport, there could be enhanced status within the internment communities.

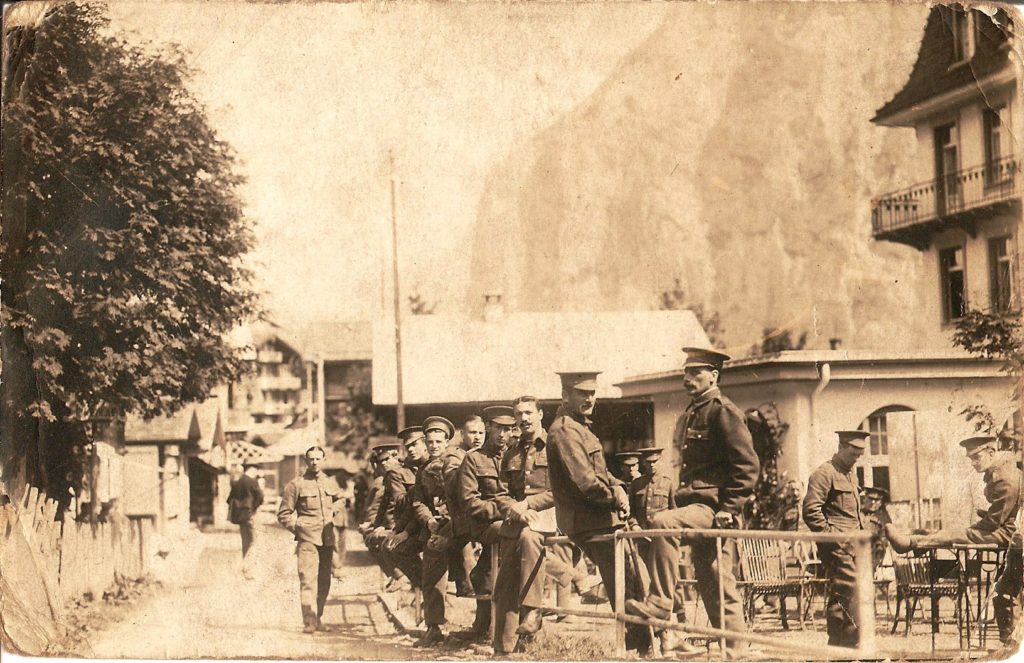

Unlike prisoner of war and civilian internment camps, neutral internment did not take place in a homosocial environment. A surprising feature of neutral internment was that those interned could have their families stay with them or visit them. As soon as internees began to arrive in Switzerland, wives and other relatives also began to appear in Switzerland. British fiancées could visit on condition they married during their stay. Officers could live with their wives and children or parents in privately rented apartments or chalets, providing they could afford to do so. These arrangements were judged to be beneficial and so it was decided that ordinary soldiers and NCOs should be able to have their wives or mothers visit them. In their home countries various charitable organisations began to raise money to pay for visits by usually female relatives who would otherwise be unable to afford the journey. The diverse experiences of family interactions are an important component of this research.

Not all internees had to wait until the end of the war to be repatriated. Those who were more seriously injured and had seen no improvement in their health while they were in Switzerland were repatriated earlier to make room for others from the prison camps. Arrangements for the repatriation of interned French, Belgian and British soldiers began immediately at the end of the war. Shortages of coal for the railways created problems transporting former-internees and also prisoners from southern Germany across Switzerland and into France on their journeys home. Rationing and shortages in Switzerland meant that it was forbidden to take some items, including chocolate, out of the country and, inevitably, a few soldiers were caught carrying contraband goods. On their homecoming, internees of the allied armies were welcomed with ceremonies and parades. Those internees who were too ill to travel remained in Switzerland in sanatoria. Some died there and never returned to their homes. The last German internees were not allowed to leave Switzerland until August 1919.

Although this is an ongoing investigation, a monograph published by Bloomsbury will be available from August 2019.